Claim: The government has placed a ban on the works of famed writer Saadat Hasan Manto for being “inconsistent with the moral, cultural, and religious values upheld by Pakistani society”. Terming his writings “explicit”, “obscene”, and “contrary to public decency and morality”, it has warned of “strict penal action” for noncompliance.

Fact: The notification is doctored; no such ban has been imposed on Manto’s works.

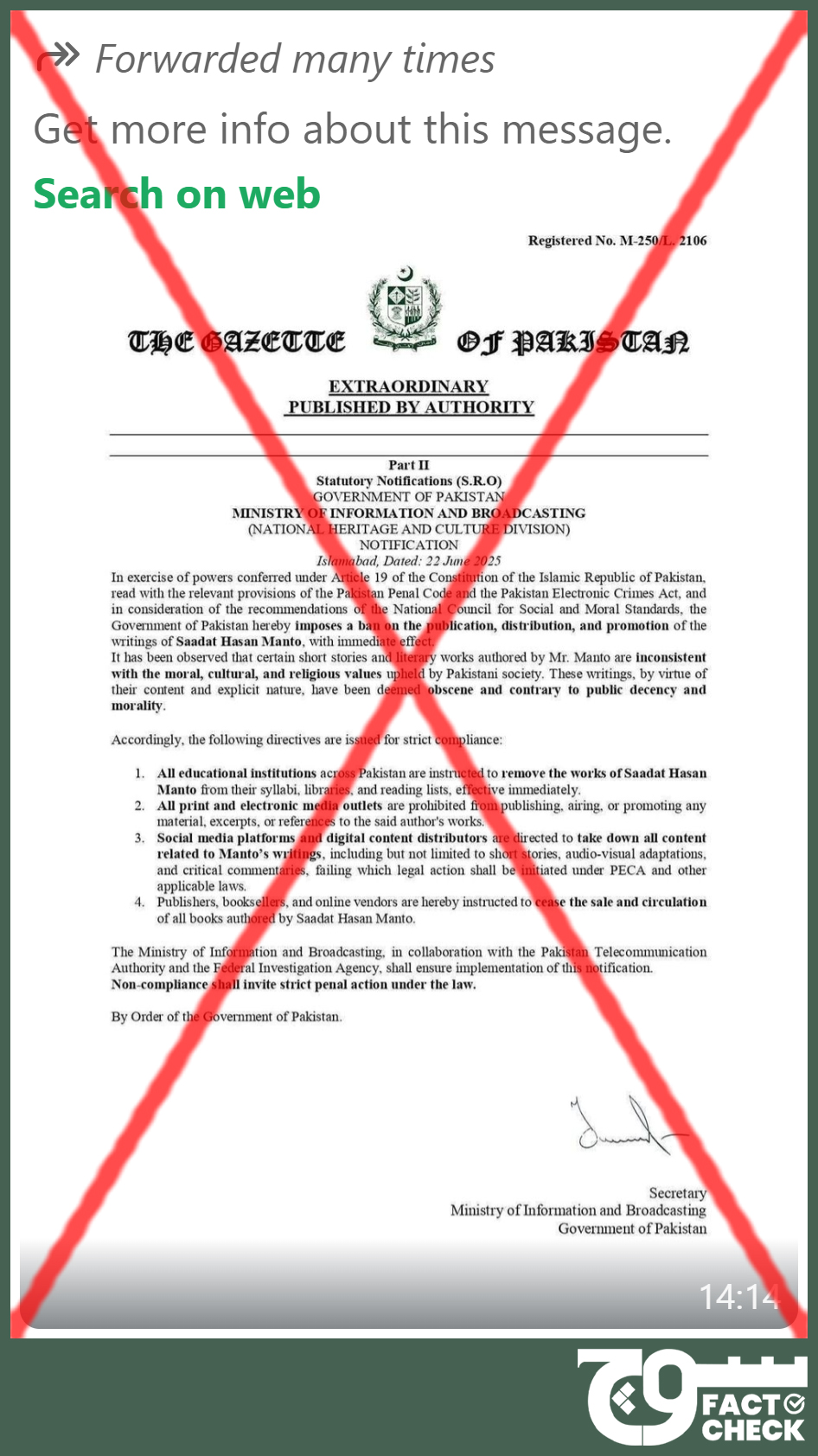

On 24 June 2025, Soch Fact Check received for verification a notification banning the works of famed Pakistani writer and playwright Saadat Hasan Manto. It was apparently issued on 22 June by the Information and Broadcasting Ministry’s National Heritage and Culture Division.

It was also shared on other social media platforms. One of the posts is captioned as follows:

“Shame and degradation be upon the persons who misunderstood and misinterpreted #Manto and banned not to be read, studied and researched. Shame shame shame Manto is the #Mirror of our history and deeds of persons like you and therefore, ban on yours please.”

The purported notification reads as follows:

“In exercise of powers conferred under Article 19 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, read with the relevant provisions of the Pakistan Penal Code and the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act, and in consideration of the recommendations of the National Council for Social and Moral Standards, the Government of Pakistan hereby imposes a ban on the publication, distribution, and promotion of the writings of Saadat Hasan Manto, with immediate effect.

“It has been observed that certain short stories and literary works authored by Mr. Manto are inconsistent with the moral, cultural, and religious values upheld by Pakistani society. These writings, by virtue of their content and explicit nature, have been deemed obscene and contrary to public decency and morality,” it adds.

The notification in question lists the following directives:

- All educational institutions across Pakistan are instructed to remove the works of Saadat Hasan Manto from their syllabi, libraries, and reading lists, effective immediately.

- All print and electronic media outlets are prohibited from publishing, airing, or promoting any material, excerpts, or references to the said author’s works.

- Social media platforms and digital content distributors are directed to take down all content related to Manto’s writings, including but not limited to short stories, audio-visual adaptations, and critical commentaries, failing which legal action shall be initiated under PECA and other applicable laws.

- Publishers, booksellers, and online vendors are hereby instructed to cease the sale and circulation of all books authored by Saadat Hasan Manto.

“The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, in collaboration with the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority and the Federal Investigation Agency, shall ensure implementation of this notification,” it adds. It also notes, “Non-compliance shall invite strict penal action under the law.”

The signature of the Information and Broadcasting Ministry’s secretary is visible on the bottom-right corner of the alleged notification.

Manto and Pakistan

Manto and his works have long been controversial in Pakistan, drawing both admiration and prejudice towards the writer. He suffered much criticism and was even put on trial three times for allegedly spreading obscenity.

“Controversy has dogged Manto and his work all through his life and beyond, especially in his own country that refuses to own one of the finest and most searing writers of the Urdu language,” according to a Dawn editorial.

“His work was censored, he was hounded by the state authorities, and even his entry into the building of Radio Pakistan … was disallowed,” it added.

Nandita Das’ homonymous film, “Manto,” which starred Nawazuddin Siddiqui and was released on Netflix in 2018, was banned in Pakistan by the Central Board of Film Censors (CBFC). The Indian director wrote that she was “disappointed” about the decision, to which then-Information Minister Fawad Chaudhry said he was “trying to pursue importers to bring this movie” to the country.

In response to a Change.org petition to the government of Pakistan to lift the ban on “Manto,” Das noted that she was “overwhelmed”.

Another homonymous film chronicling the famous Urdu novelist’s life, made by Pakistani actor and director Sarmad Khoosat, was released in 2015 and garnered success.

In 2019, the Alhamra Arts Council in Lahore cancelled the Manto Festival over alleged “bold nature” and “vulgarity” but reversed the decision later on after protests and criticism.

Intellectuals and activists have said that Manto’s work has been suppressed because of “its truthfulness”, how it “challenged the ruling class”, and because “he used to speak against dictatorship and double standards”. Some have pointed out the writer’s “non-communal views on partition” as another reason his writings are not welcomed in the country.

Interestingly, however, President Asif Ali Zardari had posthumously conferred the Nishan-e-Imtiaz — Pakistan’s highest civil award — on Manto in 2012.

This claim surfaced as ARY Digital released a teaser trailer for its upcoming drama, “Main Manto Nahi Hoon,” expected to air in July 2025.

Fact or Fiction?

Soch Fact Check reverse-searched the image but only found links to social media posts carrying the alleged notification.

The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting and the Ministry of National Heritage and Culture are separate, meaning that the latter does not come under the former. Both also have separate ministers: Attaullah Tarar and Aurangzeb Khan Khichi, respectively.

We observed that the notification mentions a “National Council for Social and Moral Standards,” but no such body exists in Pakistan.

Moreover, the signature of the ministry’s secretary, located in the bottom-right corner of the document, is exactly the same as one of the many available on Signaturely, “an electronic signature software”. Specifically, it matches the style labeled “Slanted,” which is described as “extrovert and friendly.” Based on this, Soch Fact Check concludes that it is not authentic.

We also noticed that the word “Registered” and the respective registration number on the top-right corner do not match the style typically employed in government notices, as the former is almost always capitalised and the latter is written like a fraction, above and below each other separated by a line. Evidence of the same is available in Gazette pages from 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2018, 2017, 2009, 2007, 1987, 1986, 1977, 1973, and 1965.

Besides this, when comparing the viral notification with the ones from prior years, we found multiple other discrepancies, such as:

- The name — “The Gazette of Pakistan” — is incorrectly capitalised

- The state emblem is not vertically centralised

- The text “EXTRAORDINARY” and “PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY” are incorrectly underlined

- The background of the text in most places looks different and is inconsistent with the rest of the page, which is entirely white

The following elements were also missing from the viral notification:

- The date between the two lines after “PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY”

- The text at the bottom-left corner [Code(year)/Ex. Gaz.]

- A number in brackets that appears in the centre at the end of the text

- The price in Pakistani rupees at the bottom

- The name of the secretary to whom the signature belongs

- The following text, which appears at the end of all gazette notifications: “PRINTED BY THE MANAGER, PRINTING CORPORATION OF PAKISTAN PRESS, ISLAMABAD. PUBLISHED BY THE DEPUTY CONTROLLER, STATIONERY AND FORMS, UNIVERSITY ROAD, KARACHI.”

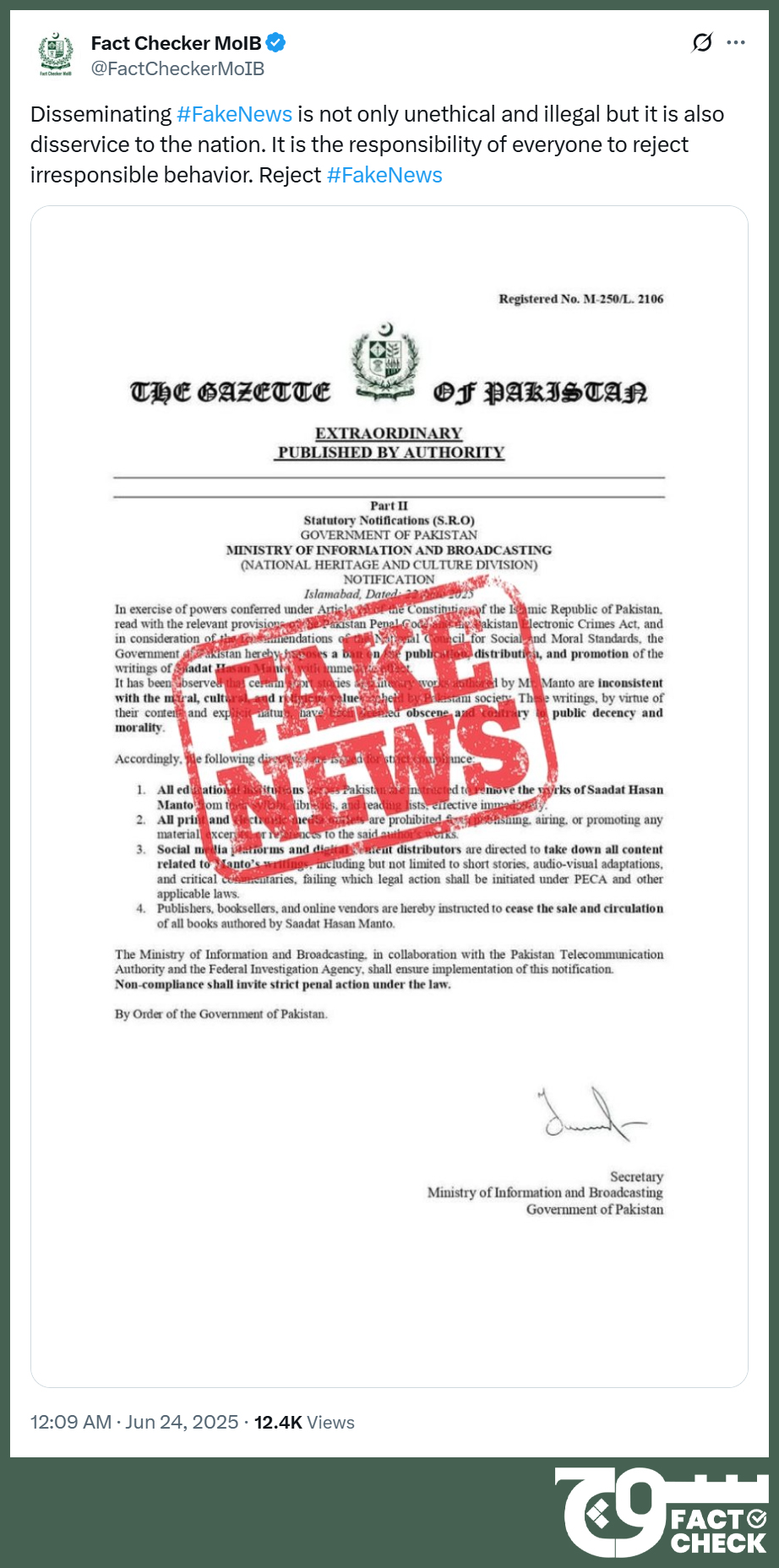

We then checked the Information and Broadcasting Ministry’s X (formerly Twitter) account and found that it had debunked the notification.

“Disseminating #FakeNews is not only unethical and illegal but it is also [a] disservice to the nation. It is the responsibility of everyone to reject irresponsible behavior,” it wrote.

Soch Fact Check, therefore, concludes that the notification is not authentic.

Virality

Soch Fact Check found the notification posted here, here, here, here, and here.

On Instagram, it was shared here, here, here, and here.

The notification was also posted here and here on X.

Veerji Kolhi, a special assistant to Sindh Chief Minister Murad Ali Shah, shared it on X and Facebook as well, saying he “strongly condemn[ed] the ban on Manto’s writings”.

Conclusion: The notification is doctored; no such ban has been imposed on Manto’s works.

Update (27 June 2025): This fact-check has been updated with additional analysis of the fake notice, comparing the format and textual elements of the doctored notification with that of the original notifications issued by the Government of Pakistan.

Background image in cover photo: Wikimedia Commons

To appeal against our fact-check, please send an email to appeals@sochfactcheck.com